Interesting write up on the Brave Browser project. I never thought much of what they were doing with crypto, and never really tried it out. I had recently installed it on some VMs to try, but I think I’ll pass given the scammy nature of replacing ads and taking people’s commissions highlighted in the article. The people running the operation don’t seem very ethical which should make you wonder what other creative ways they might come up with to make money. And it’s based on Chromium as another ding, as why not just run Chromium if I wanted to use Google’s code to begin with. Consequently, I’m still happy with Firefox locked down with uMatrix and uBlock Origin with some other settings tweaked for privacy, but not to the point that it breaks the browsing experience. The Mullvad Browser looks like it would probably be a good choice down the road if the Ladybird Browser doesn’t develop, and Mozilla doubles down on wokeness and sexual perversion.

https://www.xda-developers.com/brave-most-overrated-browser-dont-recommend/

By Adam Conway

When it comes to the best browsers out there, everyone talks about Brave Browser as being one of the best. And why wouldn’t they? It’s fast (“the fastest” according to Brave themselves), it has a built-in ad-blocker, and it supports Chromium extensions. However, Brave really isn’t special; there are countless other browsers that do so much more, and they truly maintain a commitment to privacy without buying into Google’s Chromium monopoly that the internet has to build around.

Brave has a pretty sketchy history in general, but when it comes to privacy, I’ve been glad to see tech enthusiasts begin to recognize that it may not be all it’s cracked up to be.

What made Brave so popular?

And does it do anything better than other browsers?

First and foremost, let’s get the features out of the way. Brave promises the following to users of its browser:

- Built-in ad and tracker blocking (Brave Shields)

- Brave Rewards (Earn BAT cryptocurrency for viewing privacy-respecting ads)

- Tor integration (Private browsing with Tor for enhanced anonymity)

- Built-in IPFS support (Decentralized web browsing)

- Brave Firewall + VPN (Available on mobile and desktop)

- Privacy-focused search engine (Brave Search)

- Automatic HTTPS upgrades (For secure connections)

- Cookie blocking and fingerprinting protection

- Native crypto wallet (Brave Wallet, supports multiple blockchains)

- De-AMP feature (Bypasses Google’s Accelerated Mobile Pages)

- Customizable news feed (Brave News)

- Independent video player (Blocks YouTube ads)

- Speed and performance optimizations (Uses less memory than Chrome)

- Web3 and dApp support (For blockchain-based applications)

- Goggles in Brave Search (User-defined search ranking customization)

If you’re a regular user of the internet without any interest in cryptocurrency, then most of these features won’t matter to you. Most people won’t care about IPFS, Tor, or Brave News, and the other features like cookie blocking, fingerprinting protection, and advertisement blocking are easy to achieve on basically any other browser. You can use uBlock Origin to achieve the same and more thanks to its customization, with the only benefit of Brave Shields being that it’s built into the browser and works at a deeper level than uBlock does on Chromium-based browsers.

Brave has done a fantastic job when it comes to marketing, but that’s all it is: marketing.

Even when it comes to speed, that’s a bit of a misleading point that Brave has, especially when it claims to be “the fastest” browser out there. The loading time of a page will be dictated significantly more by your internet speed and your PC’s specifications rather than the browser that you’re using. Even searching for benchmarks of Brave against other browsers gives a pretty wide range of results, including one from just last month on Reddit that claims Vivaldi is better. You’ll see this flip-flop constantly, and that’s the point. Browser speed matters very little.

None of that is to say that you should use Vivaldi instead of Brave for speed, but speed tests when it comes to browsers really don’t matter. There’s nothing inherently special when it comes to Brave which means you should use it over alternatives for a faster browsing experience. Couple that with the other features that it packs which you can get from other browsers easily, and Brave suddenly looks like just another browser in a sea of other browsers.

That is, until, we analyze Brave’s privacy claims, which appear on the surface to go above and beyond the competition.

Brave is not a privacy-oriented browser

Even if the company wants you to think it is

Let’s get one thing clear right away: Brave is not a privacy-oriented browser. It’s powered by Chromium, which is a fantastic browsing engine powering many of the world’s top browsers. If you’ve used Google Chrome, Edge, Arc Browser, or a ton of others, chances are, you’ve used Chromium. When browsers rely on Chromium as their rendering engine, that unwittingly hands control over to Google when it comes to the open internet. Even if it’s open-source, the reason Chromium works so well is that websites need to be optimized for it due to Google’s near-monopoly in rendering technology.

This already flies in the face of Brave’s commitment to an internet open and private internet, as handing the control of the internet to the world’s biggest advertisement provider inherently means giving control of the internet to a company that makes money by tracking the internet’s users. Brave claims to be built as a “user-first” browser, putting “people over tech company profit,” yet inherently supports Google in its control of rendering technology. When browsers use other rendering tech like Firefox’s Gecko engine, it forces websites to support them, rather than building a web that only Google’s engines can view.

However, that’s not the most egregious example of Brave flouting its own privacy-first model. When Brave first launched, it proposed its own advertisement network and allowed advertisements hosted on sites to be shown to the end user. The plan was to essentially replace advertisements on pages with its own through its own advertisement network, using browser-side data in order to target users. This was promptly shut down when the Newspaper Association of America, representing 1,200 newspapers, sent a cease-and-desist letter to Brave.

Brandon Eich, co-founder and CEO of Brave, called the claim “baseless” that it had intended to replace advertisements on websites with a revenue share model favoring publishers. In the same thread, he still acknowledged that it had been a talking point to journalists early on.

[M]y understanding of things from conversations since I’ve joined in July 2018 is that when Brave launched, they put out a lot of info about stuff they were _going_ to do, and one of those ideas was to replace ads. However soon after launch, a lot of folks in the company and outside of the company explained to management that this was a really stupid idea and would be scummy. So Brave never went forward with it though it was a talking point to journalists early on.

To be clear, you can view an archived page on Brave’s website which explains how the company definitely did intend to replace advertisements. It even says “[s]o we replace the bad ads with Brave Ads” right there on the page. To call it “baseless” is just… wrong.

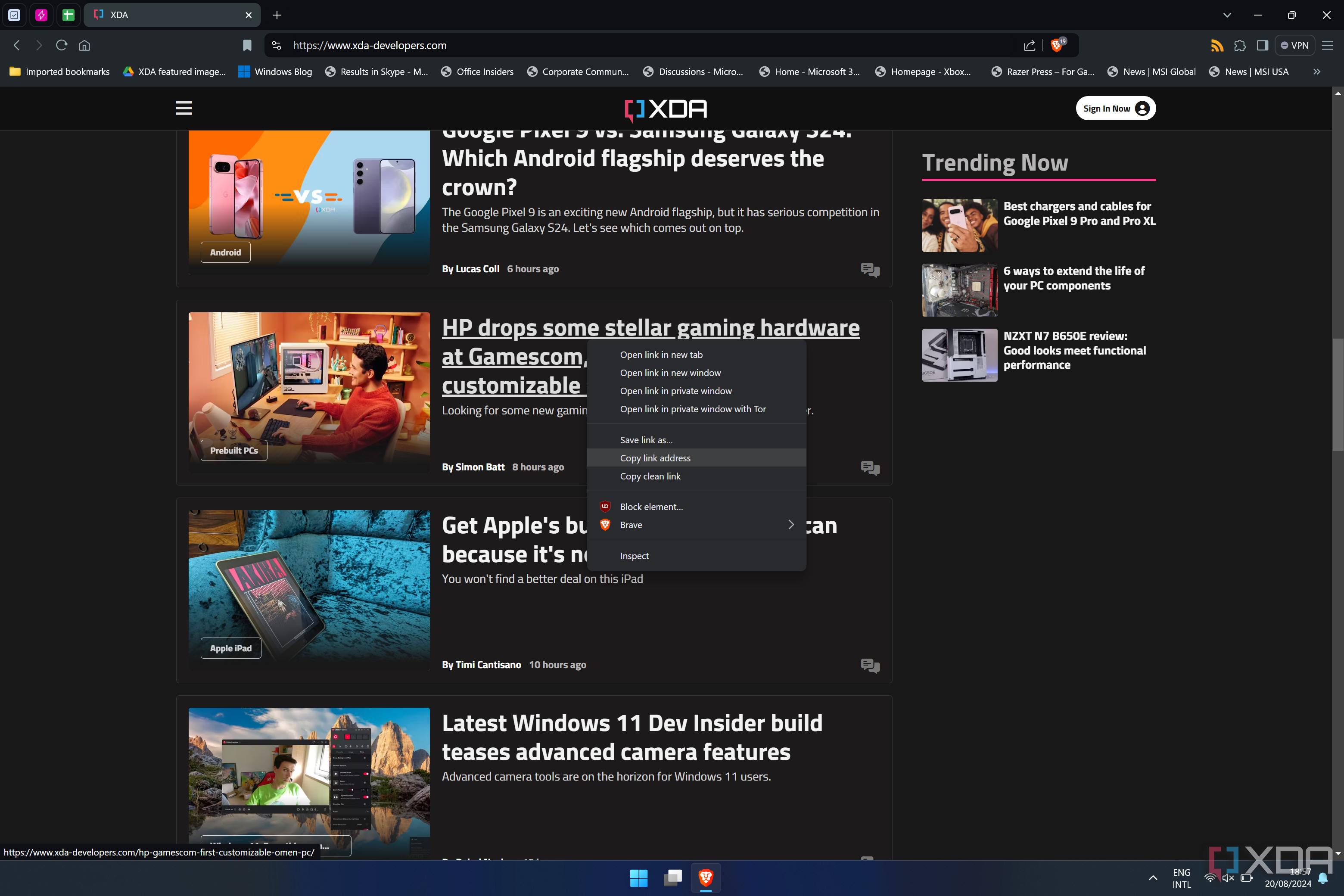

Following that, in 2020, Brave pulled a Honey before Honey even did it. When navigating to certain websites, Brave automatically placed its own referral code in the URL that the user entered, meaning that Brave got a monetary kickback whenever a user signed up and used those services. The entire point of a referral link is for the service to track the user and where they came from, which blatantly violates the privacy of the end user and flies in the face of a browser that touts its privacy above all else.

Brave has also failed to implement the Tor network correctly, where it routed DNS requests to the user’s ISP rather than through the Tor network (as an aside, you should never use Tor in anything but the official client). It installed a VPN by default on PCs, accepted donations on behalf of YouTuber Tom Scott (who claimed he had never signed up with Brave Rewards), and has had numerous Web3-related promotions and partnerships over the years. The same Web3 technology that is often associated with grifters and scams. These partnerships and promotions include:

- Partnering with Gemini, an exchange that went bankrupt after being investigated by the SEC and sued in New York, because of its Gemini Earn system

- Promoting FTX, an exchange that famously stole money from its users

- Partnering with 3XP Web3 Gaming Expo, a Web3-focused gaming expo that rewarded winners of its esports tournaments in BAT, Brave’s cryptocurrency

- Promoted NFTs by default when opening the browser via “sponsored images”

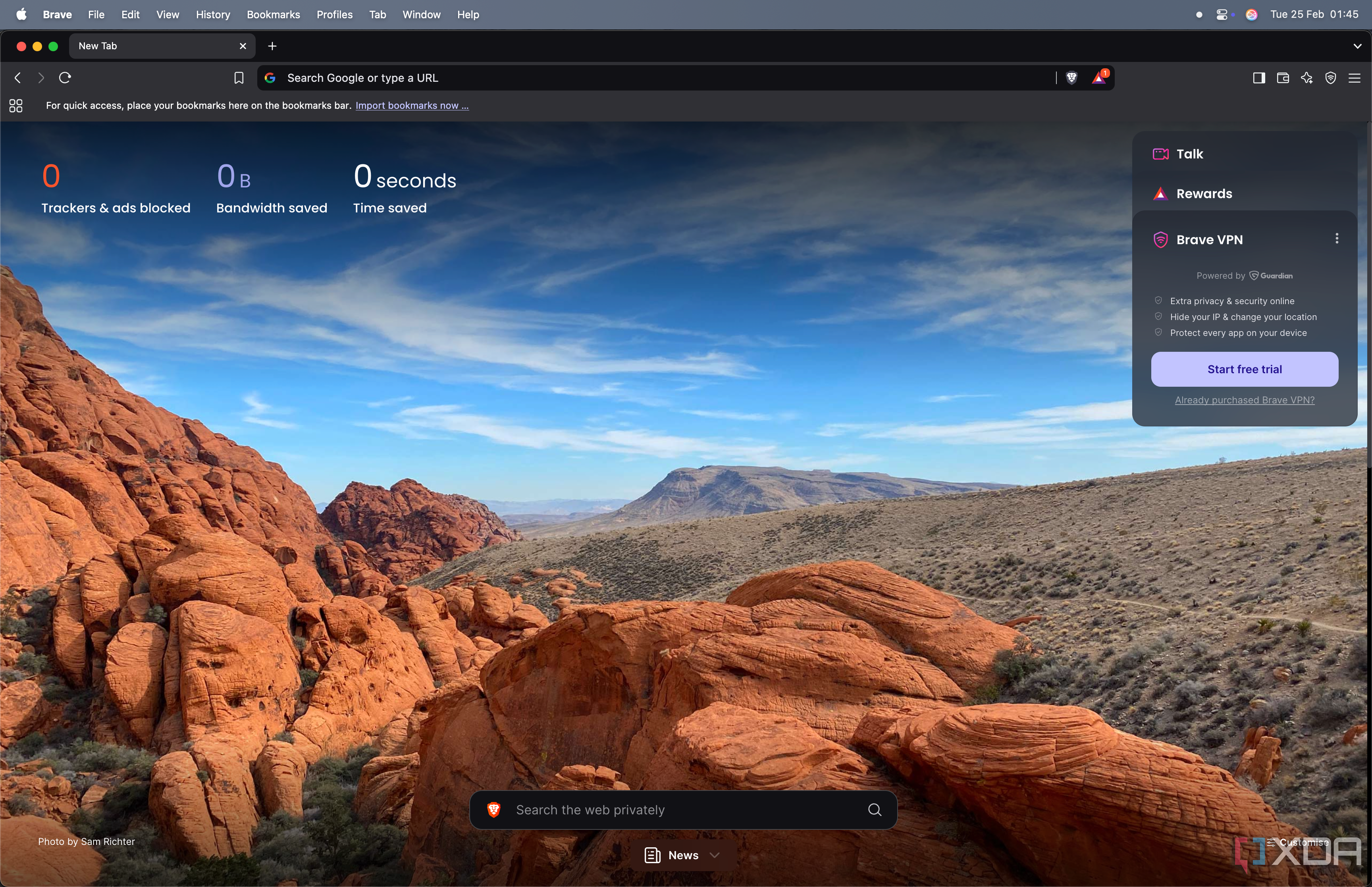

That’s another thing too when it comes to Brave; the Basic Attention Token, known as BAT, is its own cryptocurrency that users can earn by viewing advertisements shown by Brave’s own advertisement network. While you don’t have to interact with Brave’s cryptocurrency features if you don’t want to, the steps to actually take your BAT and turn it into real money are not exactly respectful of Brave’s own privacy-first model, either.

When converting cryptocurrency to real money, you need to use an exchange to sell your BAT, and the most common exchange that’s recommended is Uphold. The problem is that with any exchange that accepts BAT, you’ll need to complete a Know Your Customer check, or KYC. This requires sharing information that confirms your identity so that the service can assess your risk and also engage with law enforcement if it’s suspected that your account is being used for money laundering or other fraudulent activity.

This means that to use one of the headlining features of Brave that no other browser has and to turn your cryptocurrency that you get into real money, you need to share all of your details with a third-party service. It’s not just your name, birthday, and address either; it’s proving where your money comes from, proving your identity with an official document like a passport, and even sharing your employment status.

Considering the fact that cryptocurrency exchanges keep getting their crypto stolen (such as ByBit most recently losing $1.5 billion… oh, and Brave promoted them too), do you really trust these companies with your personal data? Again, selling your crypto is external to Brave, but BAT is on Brave’s home page, and selling it is the only way to actually give it a monetary value. It’s not a hidden feature either, and the first time you launch the browser it will show you Brave VPN, Brave Rewards, and Brave Talk. Brave says the following about BAT on its home page:

We think your attention is valuable (and private!), and that you should get a fair share of the revenue for any advertising you choose to view.

To say that the user should get a “fair share of the revenue” implies that BAT has value, but the only way you can actually realize that value is through using a third-party exchange requiring a KYC check. It either has value, which requires the user to sign up to one of those sites, or it doesn’t, but if it doesn’t, then what’s the point of Brave Rewards?

All of this is to say that it would be disingenuous at best to make the claim that Brave is a privacy-first browser, as so much of the browser’s history and continued existence flies in the face of that. I personally use Zen Browser, and there is no potential path for me that comes from the browser itself to share my personal details with anyone.

I would make the argument that a browser like Vivaldi, Zen Browser, or Floorp is significantly more privacy-oriented, as none of those browsers will even try to sell me anything, and none of them have been embroiled in multiple controversies that could leak user data. I would have also included vanilla Firefox in that list, but Mozilla has started to make some questionable moves, too.

Stop recommending Brave Browser

It’s not any better for privacy than the alternatives

When it comes to privacy, Brave has somehow managed to stay afloat with an almost cult-like following amidst controversies that would have been a death knell for any other piece of software. Even if it hadn’t made the boisterous claims regarding privacy that it has, many of these problems would still be enough to turn a user off of it. Several privacy-focused communities online are heavily against Brave for all of these reasons, and there are more problems that I didn’t even talk about in this article, too.

Online privacy is tough, and Brave’s attempt on the surface is undoubtedly at least better than using Chrome, but people who value privacy don’t just want better. There are ways you can make it significantly harder to track you online that don’t require you to use one specific browser, and it’s not as if Brave holds the keys to the kingdom of privacy online. Even in the case that you’re simply happy with better rather than the best, you can use plenty of other browsers that will give you the same experience.

Brave, in my opinion, is the most overrated browser out there. It’s easy to attack Brave on the basis of politics if you want to go that route, but the technical aspects of the project and the questionable actions that drive its development are universal. Why are some of the biggest “mistakes” ones that happened to make Brave money? It’s not a browser I feel comfortable with, and there are many options out there capable of delivering a better experience overall.