This is a very interesting case. Personally, knowing the government can violate your fourth amendment rights when you re-enter the country, I’d wipe my electronic devices before returning. They might ask to search your device, and if you refuse to unlock it, they’ll keep the device and mail it to you after they’ve made a copy of all your data. Some incorrectly think you can reboot your device where you need to enter a strong passcode,(before first unlock) which gives you extra protection, but a leaked presentation slide showed that they could hack your Android device to get in, with the only exception being a Pixel device with updated Graphene OS. I’d suspect both Apple and Google have a known exploit they won’t fix for these devices to be broken into for governments with cracking tools. Something nice with Graphene OS devices is that they have a duress passcode you can set, so you enter it or give that to authorities and the device wipes itself and I believe it can brick the device even if you desire. But if you’ve been informed they want your device and you wipe it then, you could run afoul of the law. Though you could always claim it wasn’t working properly so you factory reset it. Or you had gotten malware and factory reset it. Also, if data wasn’t encrypted or you’re really concerned about data retrieval, there are tools to wipe the leftover data still on the SSD, but encryption keys are wiped with a factory reset so they wouldn’t be able to retrieve them to decrypt the data (unless they have an exploit for the encryption method).

https://www.techspot.com/news/110560-man-arrested-allegedly-wiping-google-pixel-before-cbp.html

Wiping a device can lead to obstruction charges

By Rob Thubron

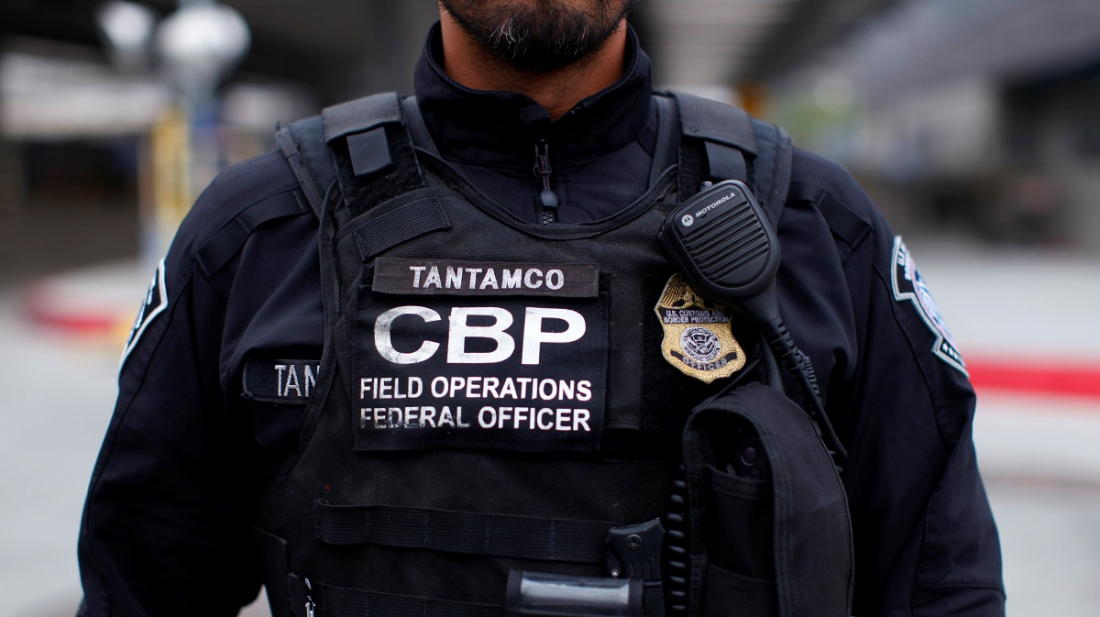

In brief: A man has been charged with destruction of evidence after allegedly erasing the contents of his phone before a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agent could search it. It’s unclear why CBP wanted to search Atlanta-based activist Samuel Tunick’s Google Pixel.

Tunick was indicted by a grand jury on November 13, and an arrest warrant was issued the same day. It says that on January 24, he knowingly destroyed the contents of the Pixel phone for the purpose of preventing or impairing government authorities from taking the property into their custody.

Tunick was arrested earlier this month during a traffic stop in Atlanta. According to a statement issued by his supporters, the musician was asked to step out of the car to observe an issue with the tail light. He was handcuffed by the officer and surrounded by the FBI and DHS.

According to the indictment, the phone was supposed to be searched by a supervisory officer from a CBP Tactical Terrorism Response Team.

The prosecution did not seek pretrial detention, and Tunick was released soon after his hearing. He is restricted from leaving Northern Georgia as the case continues.

“The arrest is totally baseless,” Kamau Franklin, executive director of Community Movement Builders, said in a press release. “The Trump administration is using political prosecution to distract from growing unpopularity in the polls, defections within the GOP, and a persistent high cost of living.”

Many Americans assume that if they wipe a phone or lock it with strong encryption, they’re simply exercising their privacy rights. But the moment an electronic device becomes the target of a lawful federal search or seizure, erasing it can itself constitute a crime – even if agents haven’t yet obtained physical possession of it.

Under federal obstruction statutes, digital data is treated no differently from physical records. Laws such as 18 U.S.C. §1519 and §2232 make it a felony to destroy or alter information to prevent federal authorities from obtaining it.

Prosecutors increasingly apply these laws to smartphones, arguing that wiping a device after officials signal an intent to search or seize it is equivalent to destroying evidence, regardless of whether the underlying investigation is serious or whether the device contains anything incriminating.

These issues are especially prominent at the US border, where CBP operates under the “border search exception” to the Fourth Amendment.

CBP can conduct basic searches of phones without a warrant, and forensic searches typically require only reasonable suspicion. Despite common assumptions, travelers have limited ability to refuse such examinations.

The law surrounding device unlocking is also concerning. Courts generally allow agents to compel biometric unlocks such as fingerprints or facial recognition, which are treated as physical identifiers.

Passcodes receive greater Fifth Amendment protection, though the government can sometimes compel their disclosure if it already knows what data it expects to find. When officials cannot obtain access, they often detain devices or pursue obstruction charges if data is erased during the process.