This is a great project mapping out automated license plate reader cameras. This will allow you to map out routes and avoid them. Though, this technology goes way back and is much more insidious than you think. I used to watch a repossession specialist who had one of these on his tow truck, and uploaded the plates and locations to his commercial provider, and he could use that database to search for targets and even figure out where they worked to get the vehicle. Throw in law enforcement and some security services, toll bridges and lanes… also having these ALPRs. So even without you carrying that smartphone, they can get a pretty good idea of your travels and where you’ve been. But visibility and pushing back is a good start for privacy.

By Jason Koebler

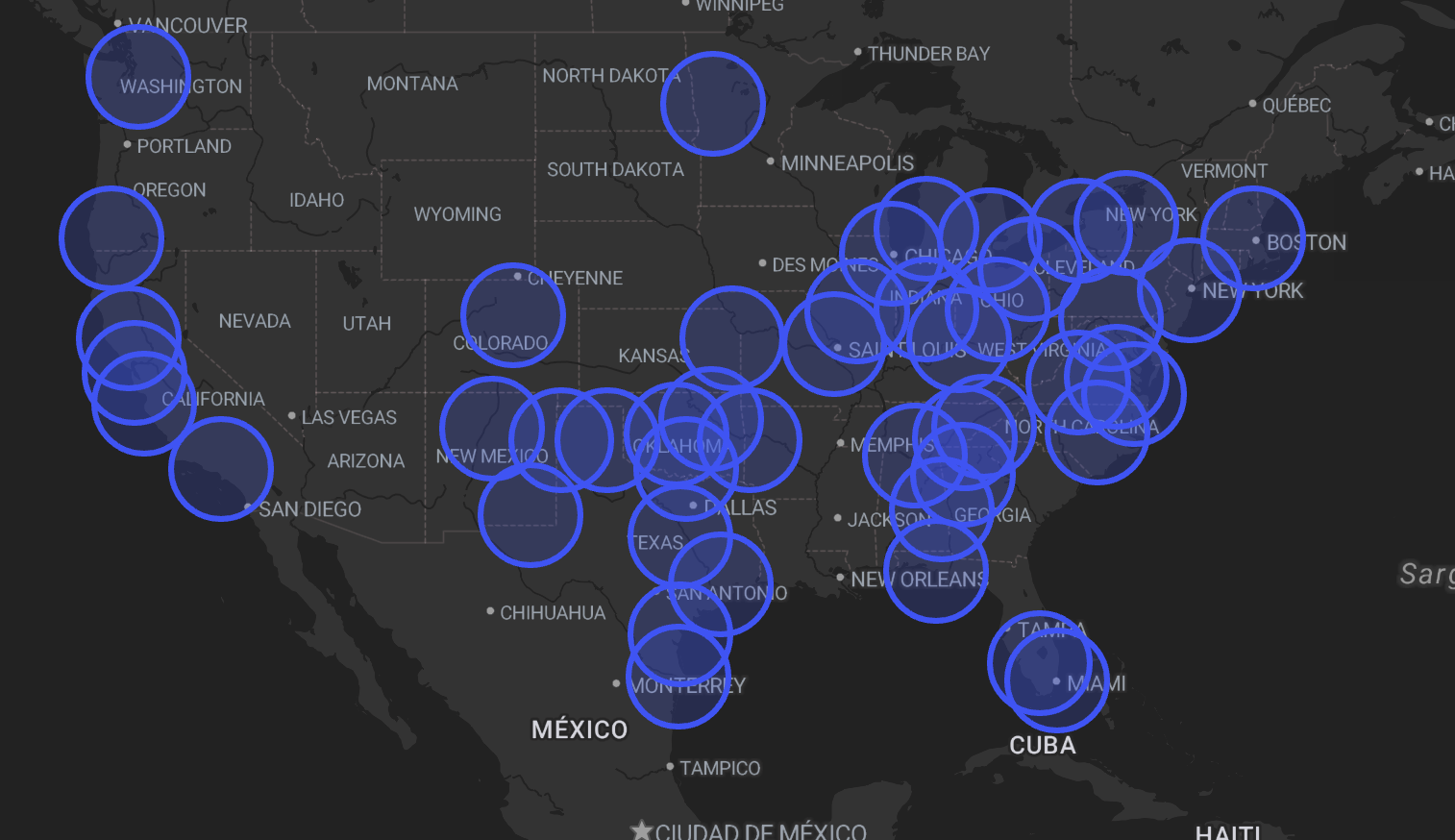

DeFlock has mapped the locations of more than a thousand ALPRs around the United States and thousands more around the world.

On his drive to move from Washington state to Huntsville, Alabama, Will Freeman began noticing lots of cameras.

“So I moved to Alabama, and on my way there, once I started getting into the South, I saw a ton of these black poles with a creepy looking camera and a solar panel on top,” Freeman told me. “I took a picture of it and ran it through Google, and it brought me to the Flock website. And then I knew like, ‘Oh, that’s a license plate reader.’ I started seeing them all over the place and realized that they were for the police. And I didn’t like that.”

Flock is one of the largest vendors of automated license plate readers (ALPRs) in the country. The company markets itself as having the goal to fully “eliminate crime” with the use of ALPRs and other connected surveillance cameras, a target experts say is impossible.

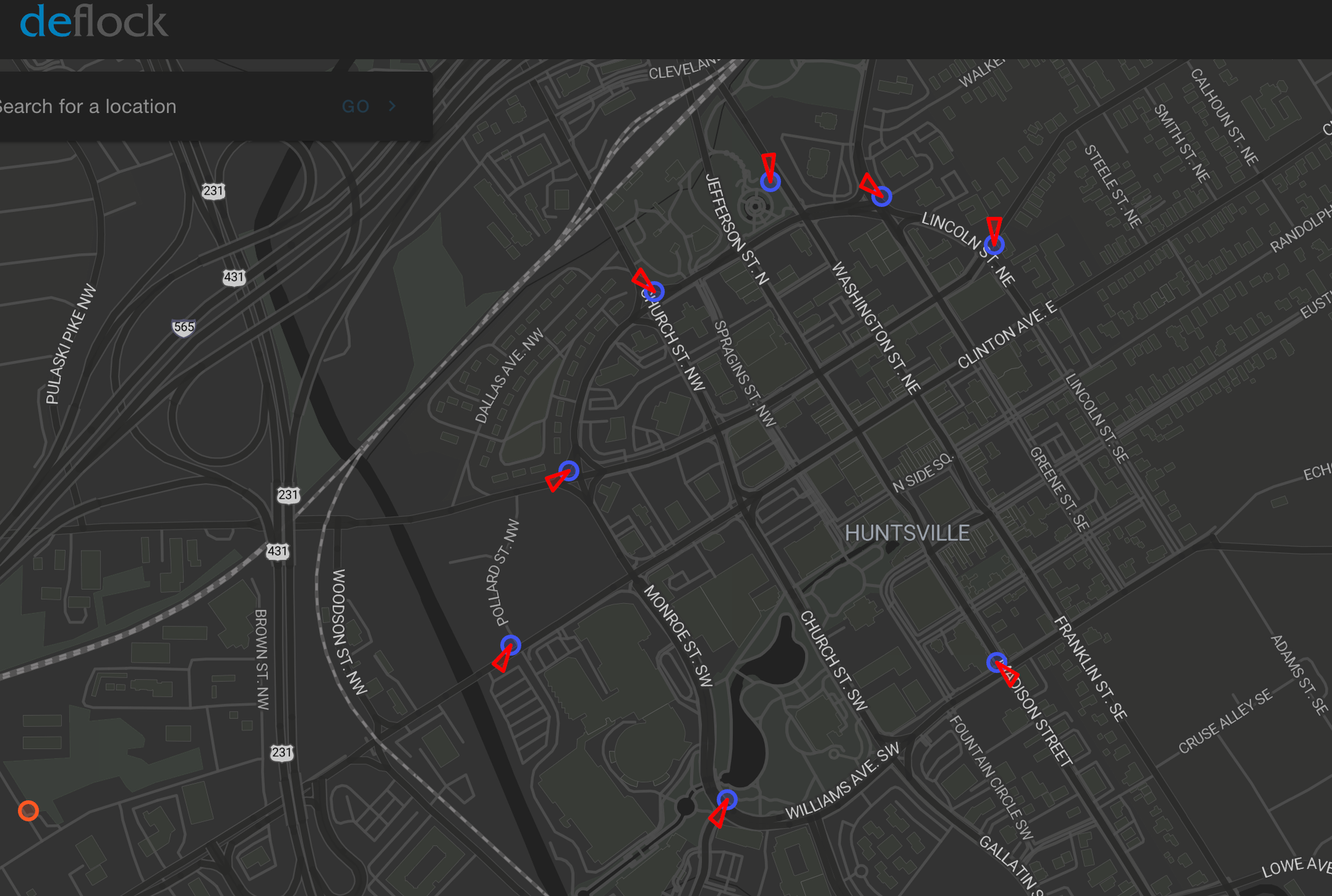

In Huntsville, Freeman noticed that license plate reader cameras were positioned in a circle at major intersections, forming a perimeter that could track any car going into or out of the city’s downtown. He started to look for cameras all over Huntsville and the surrounding areas, and soon found that Flock was not the only game in town. He found cameras owned by Motorola, and a third, owned by a company called Avigilon (a subsidiary of Motorola). Flock and automated license plate reader cameras owned by other companies are now in thousands of neighborhoods around the country. Many of these systems talk to each other and plug into other surveillance systems, making it possible to track people all over the country.

“It went from me seeing 10 license plate readers to probably seeing 50 or 60 in a few days of driving around,” Freeman said. “I wanted to make a record of these things. I thought, ‘Can I make a database of these license plate readers?’”

And so he made a map, and called it DeFlock. DeFlock runs on Open Street Map, an open source, editable mapping software. He began posting signs for DeFlock to the posts holding up Huntsville’s ALPR cameras, and made a post about the project to the Huntsville subreddit, which got good attention from people who lived there. People have been plotting not just Flock ALPRs, but all sorts of ALPRs, all over the world.

“I’ve become good at spotting them just because I’m kind of subconsciously always looking for them,” he said.

“I want everyone to be aware that this is happening. And I don’t think I can change people’s minds—some people will be fine with it. But some people won’t be,” he said. “And hopefully enough people won’t be fine with it and will do something to get them taken down [in their city] or at least better controlled, preferably taken down.”

When I first talked to Freeman, DeFlock had a few dozen cameras mapped in Huntsville and a handful mapped in Southern California and in the Seattle suburbs. A week later, as I write this, DeFlock has crowdsourced the locations of thousands of cameras in dozens of cities across the United States and the world.

“It still just scratches the surface,” Freeman said. “I added another page to the site that tracks cities and counties who have transparency reports on Flock’s site, and many of those don’t have any reported ALPRs though, so it’ll help people focus on where to look for them.”

He said so far more than 1,700 cameras have been reported in the United States and more than 5,600 have been reported around the world. He has also begun scraping parts of Flock’s website to give people a better idea of where to look to map them. For example, Flock says that Colton, California, a city with just over 50,000 people outside of San Bernardino, has 677 cameras.

People who submit cameras to DeFlock have the ability to note the direction that they are pointing in, which can help people understand how these cameras are being positioned and the strategies that companies and police departments are using when deploying them. For example, all of the cameras in downtown Huntsville are pointing away from the downtown core, meaning they are primarily focused on detecting cars that are entering downtown Huntsville from other areas.

Freeman also said he eventually wants to find a way to offer navigation directions that will allow people to avoid known ALPR cameras. The fact that it is impossible to drive in some cities without being passing ALPR cameras that track and catalog your car’s movements is one of the core arguments in a Fourth Amendment challenge to Flock’s existence in Norfolk, Virginia; this project will likely show how infeasible traveling without being tracked actually is in America. Knowing where they are is the first step toward resisting them.