This is a fascinating look into the logistics of our navy, as there is a crisis because an oiler has run aground. And how does this happen with modern electronics, GPS and detailed charts? Probably not lost on potential adversaries, but my first strikes would be to take out these oilers. All those aircraft carriers would be pretty useless if they can’t fly, and jets are enormous fuel hogs. So it would appear with aging fleets and limited resources, they might not be able to adequately deal with damaged vessels either.

Authored by John Konrad of gCaptain,

gCaptain has received multiple reports that the US Navy oiler USNS Big Horn ran aground yesterday and partially flooded off the coast of Oman, leaving the Abraham Lincoln Carrier Strike Group without its primary fuel source.

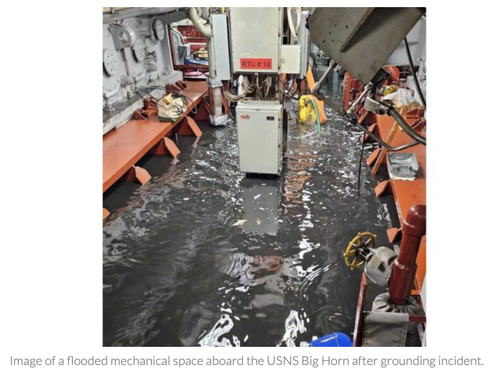

First reported on the gCaptain forum and by maritime historian Sal Mercogliano, a leaked video and photos show damage to the ship’s rudder post and water flooding into a mechanical space. US Navy vessels don’t typically transmit AIS signals, so we don’t know the exact location of the ship but a Navy source confirms she is anchored near Oman awaiting a full damage assessment.

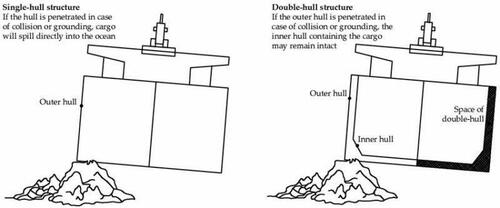

Fortunately, no injuries or environmental damage have been reported for the ship. This is significant because the 33-year-old vessel is one of the single-hull versions of the Kaiser-class oilers.

“USNS Big Horn sustained damage while operating at sea in the U.S. 5th Fleet area of operations overnight on Sept. 23. All crew members are currently safe and U.S. 5th Fleet is assessing the situation,” according to a statement from a Navy official provided to Sam Lagrone at USNI News.

It’s not looking good. I’ve been told by a shipowner the Navy does not have a spare oiler to deploy and is scrambling to find a commercial oil tanker to refuel the Abraham Lincoln carrier group.

Updates over at gCaptain forum: https://t.co/nNG6uSYGJJ https://t.co/wGP2GTYyAw pic.twitter.com/ec2oN3CpSf — John Ʌ Konrad V (@johnkonrad) September 24, 2024

Kaiser-class oilers, named after Henry J. Kaiser, were introduced in the 1980s and have long been the backbone of the Navy’s underway replenishment (UNREP) capabilities. These vessels refuel carrier strike groups and other naval assets at sea—a crucial task ensuring the Navy’s global reach and operational readiness. However, as single-hull tankers, they’ve been considered environmentally vulnerable since, following the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the 1990 Oil Pollution Act (OPA 90) mandated double-hull designs for commercial oil tankers.

The John Lewis-class, a modern replacement for the aging Kaiser-class, features double-hull construction, improved safety, and enhanced fuel capacity. Named after the late civil rights leader, these ships are designed to meet the Navy’s future logistical needs, reflecting a broader push to modernize the fleet and enhance operational resilience.

Compounding the problem is the fact that the Big Horn is the only oiler the Navy has in the Middle East. One shipowner told gCaptain that the Navy is scrambling to find a commercial oil tanker to take its place and deliver jet fuel to the USS Abraham Lincoln.

If the Navy resorts to using a commercial oil tanker as a temporary replacement, it would need to install a Consolidated Cargo Handling and Fueling (CONSOL) system for underway replenishment operations. This system includes specialized refueling rigs, tensioned fueling hoses, and high-capacity fuel pumps—all essential for safely transferring fuel to warships at sea. The tanker would also require robust communication and control systems to ensure precise coordination during refueling maneuvers.

This retrofitting process is no small feat. It requires significant modifications to the commercial vessel, enabling it to withstand the unique stresses and operational demands of pumping fuel while sailing at full speed. Moreover, a U.S. Merchant Marine crew trained in CONSOL UNREP procedures—a complex and high-risk operation—would need to be flown to the Middle East to supervise the operation. This adds another layer of complexity to an already challenging situation.

Commercial tankers are significantly slower than Navy oilers, which could leave the USS Abraham Lincoln more vulnerable to attack during aviation fuel loading operations.

The Navy currently faces a severe shortage of oilers and crew to operate them. Earlier this month, the Navy announced it might lay up 17 replenishment and supply ships—including one oiler—due to difficulties recruiting U.S. Merchant Mariners. While the Navy has launched five new John Lewis Class oilers – including the USNS Lucy Stone (T-AO 209) this week – and awarded NASSCO a $6.7 billion contract for eight more, challenges persist.

Official Navy and Military Sealift Command sources have repeatedly assured gCaptain that the John Lewis program is on schedule. However, two marine inspectors who have examined the new oilers tell gCaptain they’re encountering numerous problems, delaying the vessels’ overseas deployment. Despite the lead ship, USNS John Lewis, being launched in January 2021, it’s currently sitting idle at a repair shipyard in Oregon. As of today, none of the new oilers have been cleared to leave the continental United States.

The Broader Navy Tanker Crisis and Strategic Implications

The grounding of USNS Big Horn is a stark reminder of the broader tanker crisis facing the U.S. military, as highlighted by Captain Steve Carmel, a former vice president at Maersk, in an editorial for gCaptain last year. The Department of Defense is projected to need more than one hundred tankers of various sizes in the event of a serious conflict in the Pacific. However, current estimates indicate that the DoD has assured access to fewer than ten, a dangerously low number that threatens to cripple U.S. military operations. Without sufficient tanker capacity, even the most advanced naval capabilities—including nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, which still rely on aviation fuel—will be rendered ineffective.

This problem became significantly more accute with the closing of the Navy’s massive Pacific fuel depot – Red Hill – after poor maintenance resulted in fuel leaking into the local water supply, poisoning thousands including children, in Hawaii.

The shortage of both oilers and tankers demands urgent action. The United States must build a larger U.S.-flagged fleet capable of replenishing aircraft carriers and support joint wartime operations. Expanding the Tanker Security Program, enforcing cargo preference, and prepositioning fuel-laden tankers are potential solutions, but they require immediate implementation. With the looming threat of conflict in the Pacific, securing a robust tanker fleet is not just a logistical necessity—it’s a strategic imperative.

This crisis—coupled with the equally troubling US Merchant Marine crewing crisis—poses a significant challenge for the US Navy. Encouragingly, Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro has called for a bold new Maritime Statecraft. Moreover, with the leadershipof RepresentativeMichael Waltz and Senator Mark Kelly, Congress is working on a bill to address our maritime dilemmas—a bill this incident makes more compelling than ever. However, major obstacles remain. These solutions take time, and other federal agencies—including the US Coast Guard but most notably the US Maritime Administration under Secretary Pete Buttigieg—are under-resourced and lack motivation to do the heavy lifting required to solve these problems.

As we await the implementation of these crucial solutions, our dedicated Merchant Mariners, operating a dwindling fleet of aging logistics ships, will undoubtedly face increased operational demands and heightened pressure to work harder. More stress on the mariners and military logistics system will inevitably lead to more incidents similar to yesterdays USNS Big Horn grounding. And that’s before we even consider the Navy’s severe shortage of working ships – salvage ships, ocean tugboats, fireboats, tenders, and floating drydocks — all crucial for quickly repairing and returning damaged ships to service.