Excellent write up on trucking in Alaska on the Dalton Highway. Consequently, Roku Channel has the seasons of Ice Road Truckers to watch, and season 3 and 4 is where they showed the Dalton Highway, 2009-2010.

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/i-rode-ice-road-trucker-arctic-circle-heres-what-it-was

By Rachel Premack of Freightwaves

On July 30, I flew from my home in New York City to Anchorage, Alaska, to hitchhike to the Arctic Ocean.

I am not mentally imbalanced. I am a reporter who covers the trucking industry. Let me provide some more context: Back in May, with my colleague John Paul Hampstead, I wrote a story about the controversial growth of drilling in Alaska and its effect on the $800 billion trucking industry.

There’s a nasty freight recession slamming U.S. trucking fleets, but Alaska seems to be experiencing the opposite. Alaskan trucking executives told me in May that they’re planning on doubling in size. They want to hire not just Alaska residents, but folks from the Lower 48.

Sourdough Express, which was founded in 1898, is one of those companies looking to lavish pay raises on employees and hire more. Just this month, President Josh Norum gave his linehaul truck drivers a 25% pay bump. “[W]e are building the team for all the work the next 4 years,” he recently told me over text message.

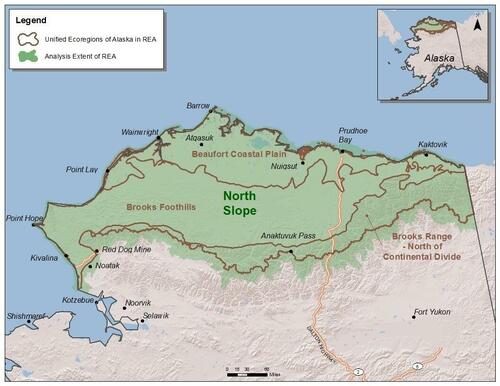

These companies particularly want more drivers to haul equipment on the Dalton Highway, which ends in the North Slope oil drilling region. It’s not a job for any ol’ truck driver. I wanted to see the experience for myself — why was it that trucking in Alaska had inspired shows like “Ice Road Truckers?” Why is everyone so fascinated by driving a truck in a really cold place? And is it as dangerous as it looks on television?

Norum advised me to come before the summer was up. So, on July 30, I took the 12-ish hour trip to Anchorage. I was only four hours behind Eastern Time but incredibly thrown off. At 10 p.m. local time, or 2 a.m. Eastern, the skies were bright blue, the sun beating down.

I fell asleep regardless. That next morning, I was off to Sourdough Express’ Anchorage terminal.

The Anchorage terminal was more hectic than I would have expected. It reminded me of other truck terminals I’ve been to in New York City — plenty of day cabs and overnight cabs alike.

Summer is actually a slower time for Alaskan trucking fleets for Sourdough. Even in the Arctic Circle, the summer is too warm to maintain the region’s famous ice roads.

Local governments create those ice roads every November and December. On that hard, frozen ground, oil company workers build and live in so-called “man camps” where they work wild shifts all winter. Truck drivers service those man camps with everything from Cheetos to drilling equipment to mattresses.

The land is too soft and squishy to support oil rigs and trucks in the summer. Instead, this season is when truckers bring up everything that oil companies will need in the winter. It’s the full-time Alaskan truck drivers who stick around, hauling pipes and steel plates that will be used in a few months. I wouldn’t be experiencing the ice roads during this trip, but if I gathered my gumption perhaps I could come back in the winter.

Then, in the winter, truck drivers from all over the U.S. come up to cash in on the lucrative, dangerous, thrilling job of being an ice road trucker. An executive at Alaska West Express, another local trucking company, told me in May that such truck drivers can make $150,000 to $170,000 a year, in addition to benefits. It’s an amazing compensation compared to the typical tractor-trailer driver, who the federal government says earns a median annual wage of around $48,000.

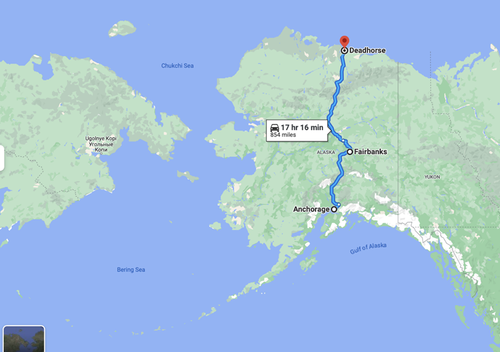

Well, anyways, before I could enjoy the Dalton Highway, I had to get from Anchorage to Fairbanks. Kyle Monnier, a 30-year-old who was born and raised in Alaska, would be my driver for that journey.

I went to the bathroom before we left. I got used to wearing this safety vest. It provides a nice splash of color to any outfit you may be wearing.

And off we went!

July 31: Anchorage to Fairbanks, 359 miles

Monnier and I would be hauling two trailers (typical for Alaska) of building supplies from Anchorage to Fairbanks. These weren’t urgent loads. The first trailer was wood and the one behind was insulation.

The first, unexpected thing I learned about trucking in Alaska is the difference in the state’s hours-of-service (HOS) laws. Federal laws require truck drivers to drive no more than 11 hours in a 14-hour period. They also need to take 34 hours off duty if they’ve driven up to 60 hours in a seven-day period or 70 hours in an eight-day period. (Here’s more information on HOS regulations if for some bizarre reason you are curious.)

HOS regulations can be a snore outside the trucking community, but they’re huge for drivers. They function totally differently in Alaska. I was shocked when I got into Monnier’s cab that he had 15 hours of driving in a 20-hour window. His on-duty time was 80 hours, too.

Alaska has extended HOS rules in part because driving here can be so unpredictable. For example, dirt roads means equipment can get unexpectedly beat up. Because Alaska is so sparsely populated, you might be waiting a while for a mechanic if you need help.

Getting out of Anchorage was quick enough, though Monnier said the traffic leaving the big city is pretty bad. Coming from New York, this didn’t look terribly congested to me.

On days that he works, Monnier drives the six hours from Anchorage to Fairbanks, unloads, and then typically drives the six hours back to Anchorage empty. He usually stops at a gas station for a simple meal. At his usual spot, I got surprisingly good chicken nuggets and a bag of chips.

I’ve reported for years about how truck drivers usually have to rely on packaged and processed foods. One thing I didn’t truly understand before riding along with Monnier is just how important energy drinks are for a truck driver. When you’re chugging along the road, you can’t exactly park at an artisan cafe or go through a Starbucks drive-thru. Instead, Monster energy drinks — or in my case, Celsius — become your main source of caffeine.

We were on the road for about seven hours, so we naturally talked for a while. Monnier’s wife and son live in the Lower 48, though she’s also from Alaska. Monnier became a truck driver shortly after graduating from high school.

After several hours chatting, Monnier played the music he normally listens to while he’s driving. He was worried I might be offended by rap music, but I am not. His music taste ended up eclectic at minimum — rap to country to electronica to “Barbie Girl.” (He has not watched the movie!) “I have listened to every song on Pandora at least 20 times,” he said.

All good things must come to an end, and eventually Monnier and I reached Fairbanks. He unhooked his load and bobtailed back to Anchorage; very little freight comes out of Fairbanks headed downstate. My day was finished, but his was only halfway over.

Aug. 1: Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay, 495 miles

I enjoyed a good night’s sleep at a Best Western Plus. The sun set at 11:02 p.m. Next on deck was the more fearsome part of the journey: Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay on the Dalton Highway. Monnier said he had gone a few times and was open to driving on it again.

I would be riding with Richard Mustain. Monnier assured me Mustain — or Mustang, as his call sign goes — was a Dalton Highway veteran, who knew just about everything there is to know about the road.

After a good night’s sleep, I arrived before 8 the next morning at Sourdough’s Fairbanks terminal.

Mustang and I would be hauling pipes for the oil fields in Prudhoe. We would also be joined by a training driver named Mike who had never gone on the Dalton Highway before.

Alaskan truck drivers call it “the Dalton.” They also all know it is exactly 414 miles. Construction on the road finished in 1974. It exists only because of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, which runs above and below ground alongside the Dalton. During the ride, I would gaze upon the pipeline as a fond friend accompanying us. In retrospect, it is incredibly odd to rely upon a pipeline as a source of mental support.

The Dalton does not begin in Fairbanks. First, you have to drive exactly 73.1 miles on another road called the Elliot Highway. I lost phone service shortly into the Elliot, and did not get it again until we reached the end of the trip. At the beginning of the Dalton, you see a series of alarming signs that make clear to anyone not driving an 18-wheeler that maybe you should bugger off: “HEAVY INDUSTRIAL TRAFFIC. PROCEED WITH CAUTION.”

I was comfortably in the passenger seat of Mustang’s 2024 Peterbilt and had no guilt about proceeding.

Truck drivers on the Dalton are dealing with steep grades in addition to heavy loads. Sourdough trucks typically haul around 110,000 pounds here – a significant bump from the typical 80,000-pound limit in the Lower 48. Oversized loads escorted by two pick-up trucks are also common here. So, when truck drivers are slowly navigating hills or curves on the road, typical passenger vehicles or motorbikes pose a safety issue.

Mustang said he typically drives around 35 mph. It’s not surprising, then, that passenger vehicles might try to skirt around him. The issue of motorcyclists and “four-wheelers” (as truck drivers call us plebeians) quickly became clear.

Mustang remained calm about 6 miles into the Dalton when a pack of motorbikes passed us. Moves on the road that might send a typical driver (not me, of course) into a fit of expletives didn’t get more than a chuckle from Mustang. Whenever the odd car appeared on the horizon, he would get on his CB radio and alert Mike behind us to keep a watch out.

Mustang is a Missouri native, a self-described “farm boy” who quit high school and started a family as a young man. He’s been a truck driver for 30 years. In 2015, a friend of his was telling a group — all truck drivers — about his experience hauling fuel. Mustang was the only one who actually went that winter. He showed up at the Fairbanks airport with a gym bag, completely out of his element.

“It was scary to come up here,” Mustang said. “I didn’t know nobody. People I didn’t know picked me up from the airport.”

He loved it immediately. He barely took photos on his phone before he moved to Alaska; now, he has about 10,000 of them. Most of them are in the same place, just different seasons. The long grasses change colors — red, pink, beige. That makes the mountains look different week to week. And then there’s the sky. Because of the ice crystals that form in the atmosphere during the long winters, “sun dogs” appear where it looks like there are three suns in the sky. Most fantastic might be the aurora borealis, which can make it look like the sky is swirling, shooting fingers down. “It will make your insides feel funny,” Mustang said.

Mustang identifies as a “cheechako,” which is Alaskan slang for someone who just moved here and is amazed by everything. After about 10 years as a cheechako, Mustang says you become a “sourdough” — not a native-born Alaskan, but a hardened resident who isn’t, say, taking pictures of the same mountain every few days.

“They come outside, look around and aren’t amazed by what they see,” Mustang said. “I’m not sure I’ll get to that point.”

John, an Anchorage resident I met after the ride-along, mentioned to me that he views himself as Alaskan, not American. Alaska is, of course, a U.S. state, but many residents here refer to the contiguous 48 states the way Canadians might. I heard folks call the Lower 48 the “States,” “America” or simply “the lower.”

“Once you start living in Alaska, you lose touch with ‘the lower’ — the last tornado, the last school shooting,” Mustang told me. “It’s like being in a different country when you live here.”

The Dalton is mostly a dirt road. Mustang told me it’s normal for a trucker’s windshield to crack during the workday because rocks fling around the vehicle’s tires and hit the windshield.

Four-wheelers and motorcyclists aside, the Dalton is truly a trucker’s kingdom. Every few dozen mileposts, there’s a spot with a nickname, likely christened by a truck driver. At milepost 74, there’s the “Roller Coaster,” featuring ups and downs. “Finger Mountain” is at milepost 98, so named because it looks like a middle finger. (I didn’t see the resemblance.) Milepost 126 is “Oh Shit Corner,” where a sharp turn may shock Dalton truckers who don’t have Mustang on the CB radio guiding them. Milepost 132 is “Gobbler’s Knob.” We are in polite company and I will not share the origin of that name.

Some signs on the Dalton pointed out these charming names, but it’s otherwise just passed down from each generation of Dalton truckers. Mustang said he’s part of the third generation of truck drivers on the Dalton. The first came in the 1970s and 1980s — guys who truly roughed it and whom Mustang spoke of with reverence. He said it took three days back then to get to Prudhoe Bay; now it can be done in 14 hours. Next, there was the next generation who trained the likes of Mustang. Mustang embraces the responsibility of training the next generation. He wears a Prudhoe Bay T-shirt most days as a sort of uniform.

Most exciting to me was milepost 115, when we officially crossed into the Arctic Circle.

I learned that the Arctic Circle, which I previously thought meant “it’s really cold,” refers to any location on Earth where the sun is up for 24 hours at least one day a year and down for 24 hours at least one day a year.

It cannot be overstated that the Dalton, and the entire state of Alaska, is beautiful. The summer is particularly fantastic. I did not see a dark sky once the entire week I was in Alaska, which is probably why I was easily delighted during my seven days there. The weather was a perfect 60 to 70 degrees.

The winter, of course, is less charming. In Anchorage, where nearly half of the state lives, the sun is up for as little as 5 1/2 hours a day. Research on Alaska suggests that depression, alcoholism and even partner abuse increase amid these dark, cold days.

“The light and dark messes with your insides, your mind, your body,” Mustang said, and luckily added, “but it doesn’t seem to bother me.”

It’s even worse in our final destination of Prudhoe Bay, where thousands work and live in the winter. The sun does not rise — at all — from late November to late January. John, the Alaskan I met later that week, told me he was an oil rig worker when he was a younger man. The big conversation during the winters in the cafeteria was whether or not you saw the sun that day.

The truck cabin was getting sunnier as we discussed all this. That’s because the trees were shrinking. We were approaching the tundra.

We were also approaching the last place where a truck driver (or trucking journalist) could get food and use the bathroom until we hit Deadhorse, the main settlement of Prudhoe Bay. It was also frankly one of the first places since we got on the Dalton that functioned as a rest stop. The town is Coldfoot.

By the way, you may have been wondering how anyone uses the bathroom when driving in the Arctic wilderness. It’s called pulling over to “kick a tire” (read: peeing next to your truck). Creative ways to use the bathroom while trucking aren’t exclusive to Alaska, but here it can get dangerous. Mustang told me of a recent episode when he kicked a tire and came back around to his truck to find a bear standing there. He charged the bear and it mercifully ran off. I do not need to tell you here that I drank very little water the day I was on the Dalton.

Exhausted and hungry, I was happy to get to Coldfoot. It’s allegedly the world’s farthest north truck stop.

Mustang warned me not to get anything fried. As previously stated, opportunities for bathrooms are limited.

Here’s the menu. I got a burger and a bowl of their soup of the day. My colleague Justin Martin, aka “Super Trucker,” noted when I showed him a picture of the menu that the prices weren’t as bad as he had guessed.

Mustang went back out to his truck to check up on his and Mike’s equipment. Meanwhile, I was kind of … confused on what to do next. We were going to sit at a communal table specifically for truck drivers, but I felt a bit out of sorts. The jet lag started to kick in and I felt a bit awkward.

Anyways, I sat down and ate my burger. Then I bought some stuff from the gift shop.

I started to get a real appreciation then for how long a truck driver’s workday is. We started the work day nearly eight hours ago, but we still had about half the Dalton left to drive. Mustang told me that a particularly active Dalton truck driver can do three trips to Prudhoe a week, which translates to about six 14-hour days and three nights away from home. Mustang sticks to two weekly trips up to Prudhoe.

Our workday was about to get a bit longer. Mustang and Mike, the trainee behind us, needed to get some work done on Mike’s truck. Coldfoot has a machine shop with a mechanic who can fix up minor equipment issues.

Ultimately, the issue was fixed. We were back on the road a bit after 5 p.m. It was longer than anyone wanted to be held up. We still had about 5 1/2 hours before we reached Prudhoe.

It’s a necessity for Dalton truck drivers to know how to do minor — or major — repairs on their vehicles. The issue on Mike’s equipment was thankfully quick and the guys were able to catch it near a mechanic’s shop, rather than on the side of the highway hours from anyone. These were brand-new Peterbilts, and the road had already given them a bit of a beating. Mustang noted to me that most trucks in Alaska have separate fuel tanks because, say, a caribou might come up and pierce one of them with its antlers. This sounded slightly ridiculous until I saw caribou later on the drive.

At 5:52 p.m., I wrote the following in my notes: “I am tired!!!”

It was time for me to wake up. We were nearing milepost 248: the fearsome Atigun Pass, nearly 4,800 feet above sea level. That’s where the Continental Divide crosses with the Dalton. In the winter, avalanches often shut down the road. Robb Christenson, the director of sales and pricing at Sourdough, warned me about this one back in Anchorage.

As we climbed the Atigun, drivers waiting to descend waited for us; this was all coordinated on the CB radio. The altitude meter clicked up and up and up.

Mustang said the Atigun is “a piece of cake.” But you need to know how to approach it. In the Lower 48, truck drivers learn that they need to shift into a lower gear when descending a hill. However, in Alaska, Mustang said instead while going downhill you actually need to go into a higher gear. It’s because drivers here are hauling heavier loads. Keeping to a low gear would just push your vehicle down the mountain and you’d risk losing control. It sounds like a quick fix, but Mustang said new drivers from the Lower 48 struggle to make this adjustment. The busted guardrails on either side of the Dalton at this stretch of the drive was a grim reminder that this stretch of highway is unforgiving to mistakes.

Anyways, Mustang indeed went into the 10th gear as we descended the Continental Divide. And here I am, weeks later, telling you the tale.

“This is the greatest trucking job in the world,” Mustang told me. “No traffic, no stoplights, just trucking. You see bears and critters and water.”

That’s great for Mustang. However, I was not doing so hot. Sitting in a passenger seat for 12 hours (without air ride!) was not ideal. For some reason, my left knee hurt. My stomach held two Celsius energy drinks, a burger, a cream-based soup and very little water. It was becoming very clear to me again why truck drivers struggle with not just food on the road, but their body literally hurting.

Combating the boredom, monotony and body aches by eating junk food seemed appropriate to me. Mustang said he once struggled with the same urges. He proudly now snacks on beef jerky and berries instead of candy bars and sips water instead of soda pop.

“It’s really easy to eat the wrong stuff while you’re trucking,” Mustang said. “A lot of depression goes on in trucking, because you’re away from your family. I love what I do but I’m way out of shape. Sitting in here, you don’t get no workout on your muscles.”

Mustang tells me we have about 2 1/2 hours left. This is the most glorious news in the world. Now that the elevation (and avalanche risk) has passed us, the pipeline has reemerged.

There aren’t too many people who live out here, as you could pretty well imagine. However, Mustang does drive to them during the wintertime, when ice roads make a slew of other communities accessible by car. Truck drivers bring food and other supplies to towns in the “bush.” These are communities of mostly Alaska Natives who aren’t connected to other settlements with roads. Until recently, people in the bush fished, hunted and foraged for food. But now, as money from drilling projects floods their communities, Alaska Natives are buying more from, say, Walmart and truck drivers are able to drive these goods to the bush towns. When there are no ice roads in warmer months, bush communities rely on planes or boats to deliver these nonperishable goods.

Not all of the residents of these bush communities are happy with these developments. On one hand, energy companies have flooded Alaska Native communities with cash and work opportunities. Subsistence living is no longer the norm. However, new issues have plagued these settlements. Alaska Native communities now see outsize rates of diabetes, alcoholism and drug abuse compared to other Alaskans.

Some local leaders say these issues are partially a result of oil development. They’re particularly concerned about ConocoPhillips Alaska’s Willow project, which could produce up to 180,000 barrels of oil a day. President Joe Biden approved the Willow project in March. That’s good news for truck drivers and oil workers but alarming for those who say the project will be a “carbon bomb” that heightens the climate crisis. Locally, some Native Alaskans say increased drilling affects traditional rites like caribou hunting. (And that would, in turn, make them more reliant on nonperishable, processed foods from outside their communities.)

Speaking of hunting, we start scanning the horizon for critters. I do spot a few caribou. We haven’t seen any bears, but they’re more scared of people than you’d think. Mustang said buffalo out here will ram your truck “until they die.” There’s another creature called muskox, which is native to the Arctic. Their fur is incredibly soft.

Before I realize it, the ride is nearly finished. I am a little sad to leave.

We are at last in the tundra. It’s not what I expected. It’s a beautiful, bright green grass dotted with wildflowers and slashed with light blue streams. Mustang tells me the fields are soaking wet. We still see some hunters nestled in the tall grasses, looking to shoot caribou. It’s unclear to me if they’re locals or came up here to hunt.

And, once again, the landscape changes. Now it’s permafrost, which is soil that remains at or below freezing even in the summer. It’s cracked because the permafrost is no longer so permanent. Even in the Arctic Circle, temperatures are rising. Even parts of the road are starting to get hilly because the permafrost is melting and expanding.

And then, against all odds, we make it to Deadhorse. The oil rigs, the squat buildings, the man camps, they all appear like a mirage.

I thank Mustang for an unforgettable experience. He admits it’s another workday for him. I fear I was an annoying passenger, or maybe he’s finally sick of Alaska, sick of trucking.

But later, he sends me no fewer than nine videos (a mere slice of his 10,000-photo library) of musk oxen, pink grasses, caribou interrupting traffic, Northern Lights and even his truck on a barge heading out to the Arctic Ocean.

“All of these videos pretty much explain why I love this job so much,” Mustang writes in his text message. He is a “cheechako” yet.