We visited the Laramie Territorial Prison yesterday, and it’s a wonderful museum with many accounts of the inmates who resided there with a lot of exhibits, weapons… If you ever go, give yourself a few hours so you can enjoy all the material. And they have a nice sized room dedicated to Butch Cassidy and his history.

It operated as a federal penitentiary from 1872 to 1890, and as a state prison from 1890 to 1901.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wyoming_Territorial_Prison_State_Historic_Site

And of interest 25% of the inmates escaped and headed west, many not being recaptured. And the sentences for murder there were in many cases shorter than they are today, and of course many were 2nd degree or manslaughter from disputes that arised.

There are a few tales surrounding how Butch Cassidy ultimately got his outlaw name. One claims that he worked in Rock Springs as a butcher. Another that it was the result of a prank with a needle gun named Butch.

By Renée Jean

This is the second in a series about the famous outlaw Butch Cassidy and his connection to Wyoming. In the first, read about how the notorious criminal found a hideout in Wyoming after his first bank robbery. The second outlines how his best friend, Matt Warner, was an outlaw early in life.

The sound of shattering glass was unmistakable. George Cassidy, who was working behind the counter at a nearby butcher shop in Rock Springs, knew instantly what that sound must mean.

Yet another brawl was taking place at the nearby gambling hall, located on Union Pacific property.

Cutting meat was perhaps not the most glamorous of occupations for a young lad fresh off the successful robbery of the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride in June 1889.

But saloon brawls could be plenty exciting.

And someone might need his help.

So, as he would often do, Cassidy did not run away from the sound of trouble. He ran right toward it, meat cleaver in hand.

Once in the saloon, Cassidy could see a mob threatening the life of a man named Harry Parker, who would later become a deputy marshal in Rock Springs for a couple of years.

Cassidy shouted at the mob in a booming voice, raising his cleaver high above his head, urging the menacing miners to knock it off.

The sight of a stocky, but awfully young butcher waving a meat cleaver overhead was only a momentary distraction for the mob.

But then came the distinctive metallic smacking sound of a Winchester rifle slamming ammunition into place.

Locked and loaded.

A man name George Pickering, who served at one time as a Union Pacific policeman and later as a city marshal, had shouldered his rifle, ready to fire at the first man who made a wrong move.

And just like that, the brawl was no longer worth it.

The drunken mob dissipated, and no one was hurt after all.

Clues From The Pinkerton Manhunt Series

The account is based on an oral history taken by Cassidy’s little sister, Lula Parker Betenson, from Harry Parker’s son, Pete.

Later historians, trying to piece together the exact time frame of this story have run into trouble documenting the tale Parker told Betenson and various other newspaper reporters of the day, but Pete Parker wasn’t the first to say that Cassidy worked at one time as a butcher in Rock Springs, so the tale cannot be entirely refuted.

The first mention came from one David C. Thornhill, who joined the Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1883, retiring as its vice president in 1938.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency was a private security and investigative agency, established in 1850, that grew to become the largest private law enforcement contractor in the United States.

When Union Pacific decided it really wanted Cassidy and his Wild Bunch, it was to Pinkerton they turned, the detective agency whose logo was an unblinking eye, and whose motto was that they never sleep.

Before dying in 1942, Thornhill gave several lengthy interviews to American Weekly, which ran a series in 1943 it called, “Manhunting with the Pinkerton’s.”

One article in the series was a lengthy piece on Cassidy, in which Thornhill claims that Cassidy acquired the name the world would come to know him by, Butch Cassidy, due to the time he spent working as a butcher in Rock Springs.

Some historians from Browns Park, an isolated valley between Utah and Colorado that was one of Cassidy’s most important hideouts, say Cassidy worked for a Rock Springs butcher connected to Browns Park rancher Charlie Crouse, feeding rustled cattle meat into Rock Springs.

Narrowing down exactly which butcher shop Cassidy worked with or for has proven quite difficult, however.

For much of his Wyoming years, Cassidy seemed to be trying to, if not walk the straight and narrow, at least lay legitimately low.

Newspapers of the day weren’t too interested in writing ho-hum stories about an unassuming young man, no matter how blonde, blue-eyed, and charismatic he might have been. There was also a fire during the relevant timeframe, which wiped out a massive portion of the every day record Rock Springs newspapers would have published.

Major stories from Rock Springs newspapers would be picked up by other newspapers in the region. But not those cute, little tattle-tale stories from the country correspondents, who so delighted in reporting the lesser gossip about who went where to visit whom and for what purpose.

Historian Mike Bell, in his book, The “Butchers of Rock Springs,” has narrowed the likeliest butchers who Cassidy worked for or with down to two, from what he describes as an extremely weak field of contenders.

His picks are William Gottsche — possibly working alongside Otto Schnauber — or Jonathan Mawlson. And his pick for the most likely timeframe for Cassidy’s butcher shop years in Rock Springs is the winter of 1892/93.

But it also could have been before the Telluride Robbery, according to some accounts, including Thornhill’s. Or it could have been after his 1894 to 1896 stint in prison. Or perhaps it didn’t happen at all.

It just depends on which historian one reads.

Some of the old butcher shops are still standing in Rock Springs to this day. They’re detailed in a self-guided walking tour that is available from the Rock Springs Historical museum.

Included on the tour as well are the offices of Douglas Preston, one-time Wyoming attorney general, and Cassidy’s lawyer.

The museum is interesting as well, with not only an exhibit on Cassidy, but also the jail it built in 1894. It’s possible he would have been kept in that jail, if the timeline for these Rock Springs stories is after his incarceration at Fort Laramie.

The site of William O’Donnel’s Meat Market, which operated in 1889, Otto Schnauber changed the name of the business to Pacific Meat Market in 1897. (Renee Jean, Cowboy State Daily)

Turning Toward The Outlaw Trail

Thornhill also told one other Cassidy tale that may explain his abandonment of the straight and narrow path he appeared to have been walking after the Telluride robbery, working on several ranches as a cowboy and then potentially as a Rock Springs butcher in the winter of 1892/93.

According to what Thornhill told American Weekly, Cassidy had been falsely accused of rolling a drunk in Rock Springs, relieving him of his money after spending the night drinking with him.

For Cassidy, this kind of crime was shameful and beneath him. Nor does it sound at all like any of the other stories people tell of Cassidy, where he tended to help those in trouble, even at his own expense.

Throughout his career, Cassidy declined to rob chump change from everyday men and women. He wanted huge paydays from bigwig executives — men he saw as part of a corrupt system that made it hard for the little guy to prosper.

He would never stoop to robbing pocket change from a poor old drunk — and indeed, the court could produce no actual evidence against him, resulting ultimately in his acquittal.

Historian Charles Kelly, in his book “The Outlaw Trail,” says the false charge for such a low crime made Cassidy so angry he “cursed the officers, the judge, the town of Rock Springs, the county of Sweetwater, and the entire state of Wyoming” after the verdict, vowing to take revenge in open court.

Cassidy’s revenge may have included stealing a herd of horses from a nearby ranch, according to the story Thornhill told American Weekly — a story that matches details told by Warner in his memoir, “Last of the Bandit Riders,” as well as Kelly’s “The Outlaw Trail.”

According to the tale, Cassidy was arrested, but managed to trick his captors and escape with all their horses, as well as the herd he’d stolen.

But, when he realized he’d also taken the lawmen’s water canteens — which would be certain death for them — he turned around, returning both water and horses, on the condition they not follow him, before riding away.

The three stories as told by Warner, McCarty, and Thornhill all take place at different times and locations. None of the men offer any particular documents or records corroborate this story either.

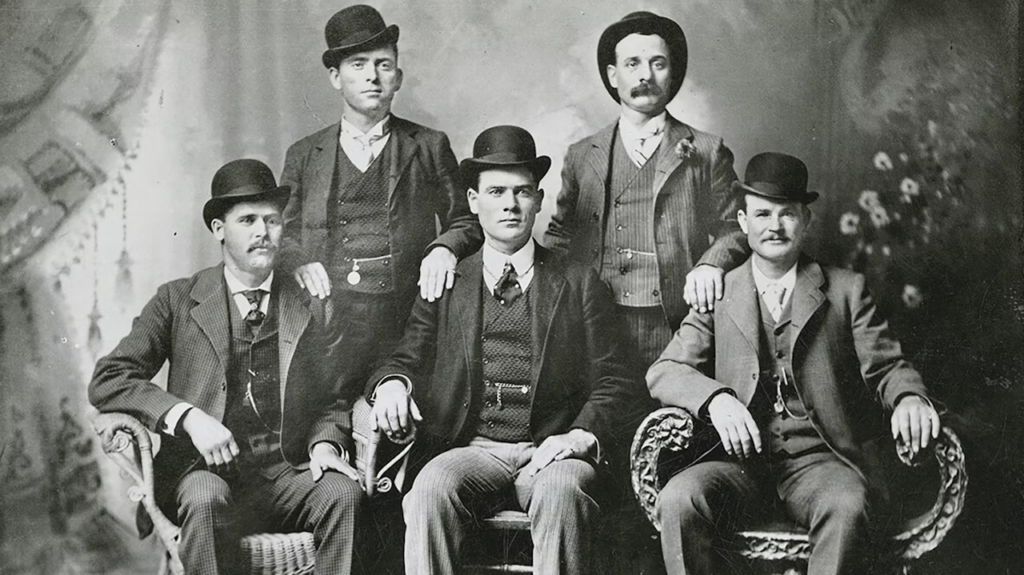

The infmaous Fort Worth Five, with Butch Cassidy pictured bottom right. (Getty Images)

The Last Laugh

Warner provides one other tale from oral history that describes how Cassidy came by the name Butch.

In his memoir, Warner says he, McCarty and Cassidy were headed “hell-for-leather” to Thompson Springs after the Telluride bank robbery. Somewhere in eastern Utah, they stopped at a shallow lake with a rock jutting up from the middle, to let the horses rest for a moment and drink their fill.

Cassidy, who was going by the name Roy Parker at the time, was standing on a rock that hung out over the lake’s edge. That gave Warner, who had a fondness for playing pranks, an idea. It would be just as funny as the time he’d robbed that merchant in Brown’s Park, inspiring a wild masquerade ball

Warner had a needle gun, a style of rifle with a needle-like firing pin, that he took to calling Butch because the long-shelled shotgun had an absolutely furious kick back.

“I saw what the gun would do to Roy if he fired it while he was standing there on that sloping rock,” Warner wrote in his memoir.

So, he placed another little bet, just like the horse racing bet he’d placed when the two men met in Telluride, one that he knew Cassidy would take without thinking twice.

Pointing at the rock jutting up from the shallow lake, he said, “Bet you can’t hit that rock out there in the lake.”

Cassidy scoffed. Hitting that rock would be no challenge, he told Warner, firing off a shot at the same time.

Just as Warner had expected, Cassidy landed flat on his back in the mud and water.

“He flopped and floundered like a fish, and by the time he was out, he was smeared with mud from his head to his feet,” Warner wrote in his memoir. “Tom and me nearly fell off our horses laughing. We named him Butch after that kicking needle gun.”

Warner never mentions any time that Cassidy spent working in Rock Springs as a butcher. But, on the other hand, Warner and Cassidy would also separate not long after the Telluride bank robbery.

After spending a little time in Brown’s Hole and Robber’s Roost, the three men believed they’d shaken the law off their trail.

Warner and McCarty were anxious to rejoin society and spend some of their loot. But Cassidy didn’t feel the same way about that. He was certain a pub crawl at this point was reckless. He wanted to lay low a while longer.

Cassidy would prove right this time, and so, perhaps, the last laugh was his.

McCarty and Warner no sooner hit up the saloons in Lander, Wyoming, than they received word from friends that the law was headed straight for them. They had tied their horses out back, just in case, and managed to just get away.

The law chased them all the way into Star Valley, just ahead of snow closing the pass.

Safety, at least for the winter, was theirs.

Warner and Butch would not rob any more banks together — each being stuck in prison while the other was free — though they would eventually ride together one last time.